Street photography, as an artistic genre, has been around for over a century, evolving with changes in technology, art, and culture. At its core, street photography captures candid moments of everyday life in public spaces, and it has become a vital part of visual storytelling and documentary photography. Street photography can be a valuable tool in exploring unique identities and culture of regions and communities, particularly in times of social growth and strife. Street photography is a tradition that dates back to the invention of photography. The invention of photography in the early 20th century coincided with the urbanization and globalization of the world. It can be said that the pace of change in social and cultural demographics has picked up during the 20th and 21st centuries and street photography provides a wonderful (and at times, discreet) way of documenting our way of life for future generations.

The Birth of Street Photography

As everybody knows, photography was born in Paris. It seems reasonable to assume that also Street Photography also finds its roots in Paris.

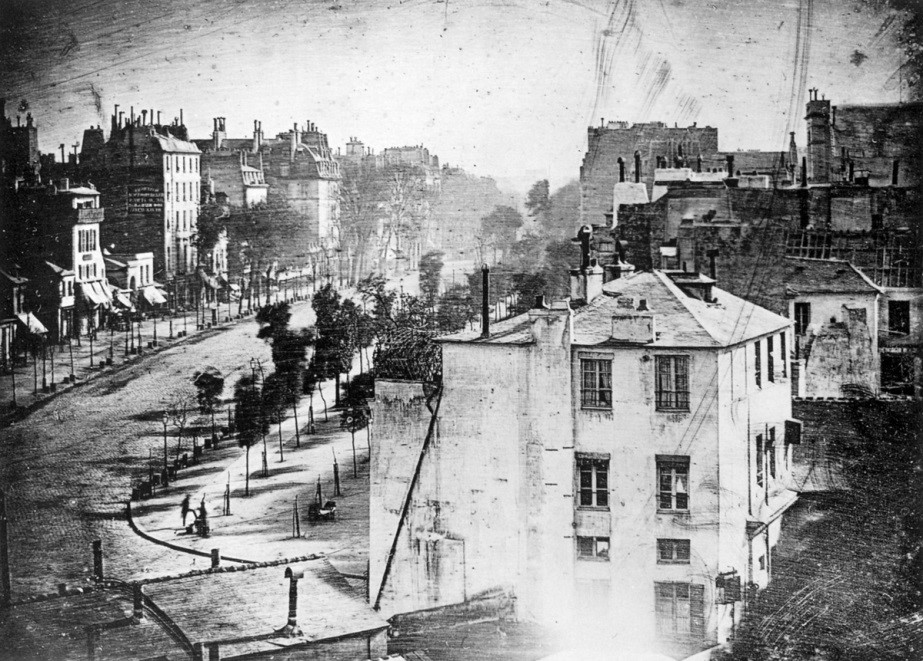

Louis Daguerre and the First Street Photo

But the very first Street Photo was this one here above, taken by Louis Daguerre, who was trying to capture Boulevard du Temple, few steps from our gallery in Paris. Taken in 1838, or in 1839, according to different sources, this is believed to be the earliest photograph showing a living person. The street was busy, but since the exposure lasted for ten minutes the moving traffic left no trace. Only the two men near the bottom left corner, one apparently having his boots polished by the other, stayed in one place long enough to be visible. As with most daguerreotypes, the image is a mirrored negative that appears as positive when no reflections of bright light disturb the view on it.

So the start of photography was the start of street photography. Street photography also used to be a solitary activity, with few photographers collaborating and sharing their prints with one another. Street photographers do not necessarily have a social purpose in mind, but they prefer to isolate and capture moments which might otherwise go unnoticed.

Charles Nègre And Early Experiments

French photographer Charles Nègre used his camera to document architecture as well as shops, labourers, traveling musicians, peddlers, and unusual street types in the 1850s. Because of the comparatively primitive technology available to him and the long exposure time required, he struggled to capture the hustle and bustle of the Paris streets. He experimented with a series of photographic methods, attempting to find one that would allow him to capture movement without a blur, and he found some success with the calotype, patented in 1841 by William Henry Fox Talbot. The calotype could capture an image in one minute, a stunning efficiency when compared with the 15 to 30 minutes required for a daguerreotype. Some of Nègre’s photographs were staged to evoke action, and some occasionally included accidents—a blur of a figure moving across the composition. Those accidents serve as some of the earliest examples of movement captured in the still image, an expression of the energy of the street.

When Painters Turned to the Street

The impulse to visually document people in public began with 19th-century painters such as Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who worked side by side with photographers attempting to capture the essence of urban life. Some used photographs as an aid to their painting.

André Kertész: Spontaneity in Composition

André Kertész, widely considered one the most influential photographers of the 20th century, is known for using innovative camera angles, unexpected lighting, and up-close cropping that often abstracted his subjects. He mastered the ability to capture spontaneous activity without sacrificing thoughtful composition. In the 1930s Hungarian photographer Brassaï began to gain a reputation for his night photographs. Brassaï’s photographs of the Paris underworld illuminated by artificial light were a revelation, and the compilation of the series that he published, Paris After Dark (1933), was a major success.

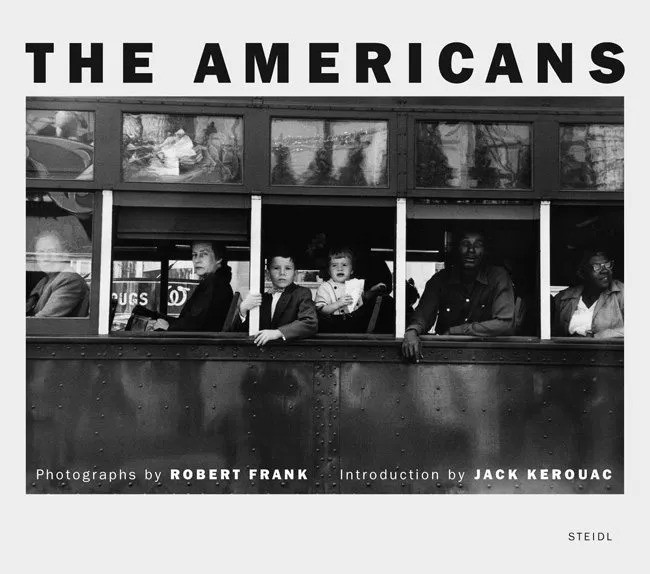

In the 1950s and 60s, street photography flourished, thanks to the rise of faster, more accessible cameras and film. Photographers like Robert Frank and Garry Winogrand captured the spirit of post-war America, documenting the changing social and political landscape of the country. Robert Frank’s 1958 book, The Americans, was significant; raw and often out of focus. The Americans and Frank paved the way for new forms of expression, new formats of display, and an artistic freedom among photographers that endured into the 21st century.

Eugène Atget, another early street photographer, documented the streets of Paris in the late 19th and early 20th centuries before they were demolished and rebuilt according to the new city plans implemented by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Atget made albumen prints using a large-format view camera that he lugged with him throughout the city. In contrast to Atget, photographer Charles Marville was hired by the city of Paris to create an encyclopaedic document of Haussmann’s urban planning project as it unfolded, thus old and new Paris. While the photographers’ subject was essentially the same, the results were markedly different, demonstrating the impact of the photographer’s intent on the character of the images he produced. Atget’s goal was to document old Paris before it vanished, regardless of what replaced it. Given the fine quality of his photographs and the breadth of material, architects and artists often bought Atget’s prints to use as reference for their own work, though commercial interests were hardly his main motivation. Instead, he was driven to photograph every last remnant of the Paris he loved.

In the United States just before World War II, several photographers, including Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Berenice Abbott, were starting their careers and beginning to more clearly define the potential of photography as it would be practiced in full force a decade later. It was during that period that street photography really began to take form as a unique subgenre of documentary photography.

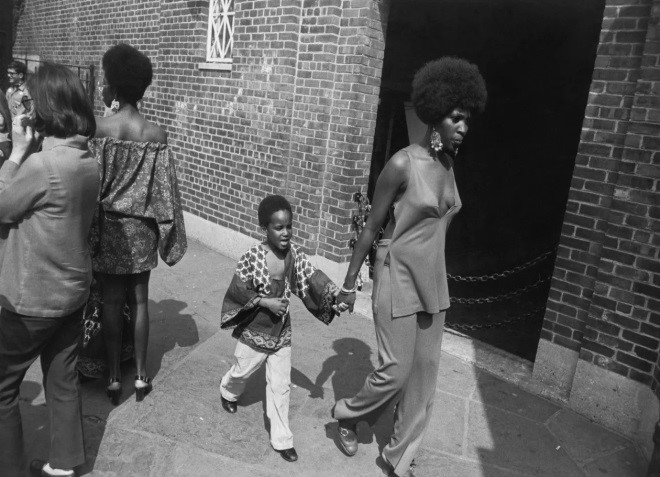

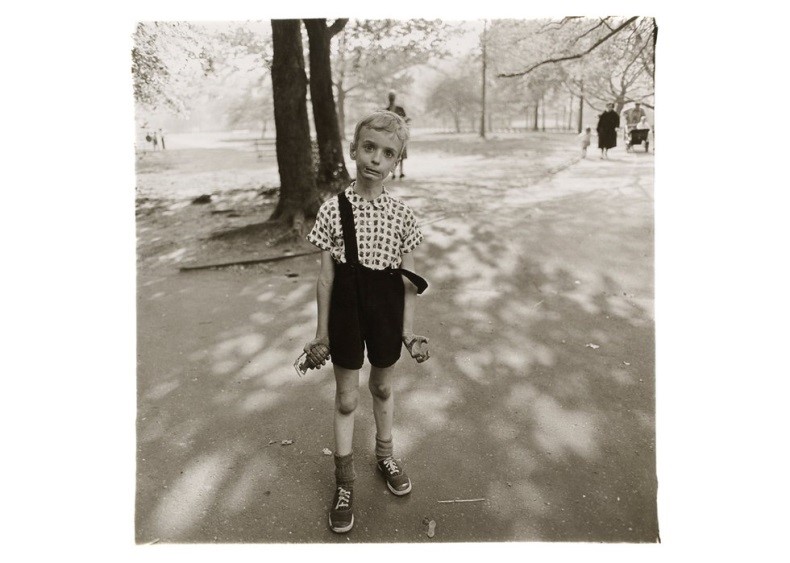

The 1970s saw street photography become more introspective, with photographers such as Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander exploring themes of identity and alienation in their work. The definition of street photography (or photographer) is also different from 1918 to today. In Edwardian times it used to be a photographer who would take portraits on the street for a fee. During the two World Wars, the format could also have been argued to be under the umbrella term of ‘war photography’ and possibly photojournalism. Aside from journalists, ordinary people and hobbyist’s priorities did not tend towards luxuries such as film for their cameras (if they could afford one) during these tough years. Post war saw the growing affordability of cameras and the consequent boom in candid and social documentary photography. French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, an admirer of Kertész, is often credited with bridging art and documentary photography. Cartier-Bresson was a champion of the Leica camera and one of the first photographers to maximize its capabilities. While discussing his work, Cartier-Bresson coined the phrase “the decisive moment,” which resonates particularly well with the street photographer’s aim: taking advantage of that split second in which the elements of a photograph come together with clarity. Photographers such as Henri-Cartier Bresson and Diane Arbus who documented the everyday weird and wonderful in the 1950’s were probably the pioneers of what we are familiar with today. William Klein, Lisette Model, Weegee, Garry Winograd, Thomas Hoepker, Lee Friedlander, André Kertész, Dorothea Lange, Berenice Abbott and Vivian Maier . . . are among the best-known chroniclers of this genre.”

Key movements in the history of street photography, each characterized by distinct stylistic and thematic focuses:

- Pictorialism: Emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, characterized by a soft focus and painterly aesthetic. Pictorialist photographers captured street scenes and everyday life with an emphasis on visual beauty.

- The New Vision: Emerged in the 1920s, focused on formal elements of photography such as lines, shapes, and patterns. New Vision photographers experimented with angles and perspectives to create abstract and surreal images.

- Humanism: Emerged in the 1930s, emphasized human emotion and experience. Humanist photographers captured candid moments of people in public spaces, reflecting the struggles and joys of everyday life.

- Documentary: Emerged in the 1930s, focused on social issues and political events. Documentary photographers used photography as a means of activism, capturing images of poverty, war, and social injustice.

- Modernism: Emerged in the 1950s, emphasized aesthetic qualities of photography such as light, shadow, and texture. Modernist photographers captured abstract and minimalist images of the urban environment.

- Postmodernism: Emerged in the 1980s, rejected traditional conventions of photography. Postmodernist photographers used irony and humor to critique society and challenge the idea of photographic truth.

While these movements are not mutually exclusive, they represent distinct approaches to street photography, each leaving a significant impact on the genre’s development.

In the digital age, street photography has undergone another evolution, with photographers using smartphones and social media to share their work and connect with a global audience. With the proliferation of social media platforms such as Instagram, Pinterest, Flickr, and others, street photography has become more democratic, accessible, and inclusive practice than ever before.

Here are a few contemporary street photographers:

Brandon Stanton (Humans of New York): Stanton interviews and transcribes the lives of New Yorkers he meets on the streets of the city and provides intimate insight into the colloquial saying, “can’t judge a book by it’s cover”. His Instagram account acts as a visual anthology of the lives who make the fabric of New York.

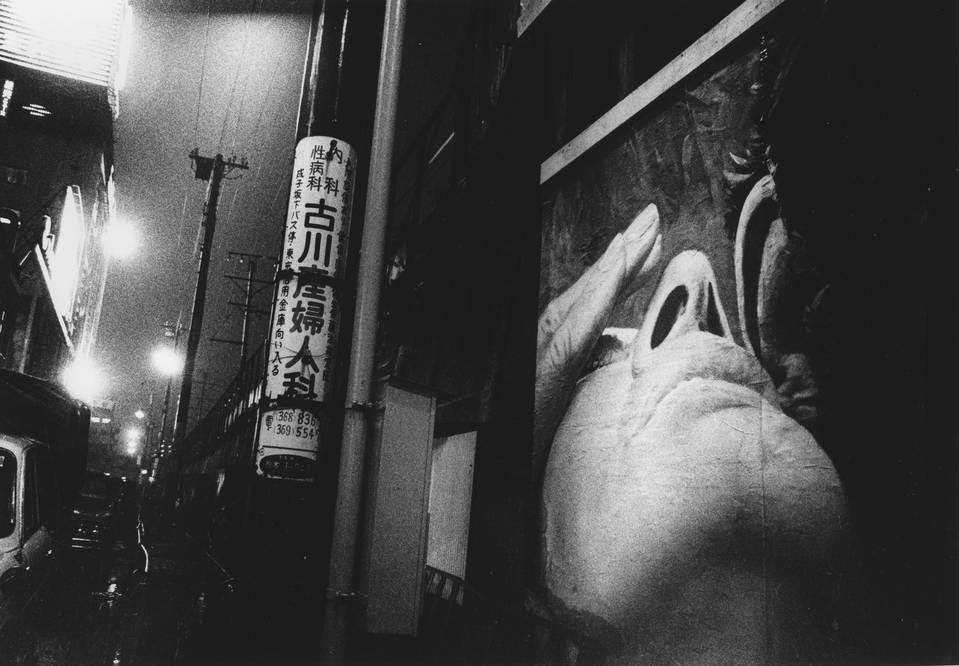

Daido Moriyama: Moriyama is a Japanese photographer known for his gritty, black and white images of Tokyo and other urban environments. His work often features abstract and distorted images that capture the energy and chaos of modern life.

Alec Soth: The American photographer is known for his large-format color photography that often explores themes of American life, identity, and community. His photographs often have a cinematic quality, as he captures people and places in a way that suggests narrative and emotion.

Throughout its history, street photography has been a powerful means of capturing the essence of life in public spaces, reflecting the cultural and social changes of the times. As a genre, it continues to evolve, reflecting new technologies, art forms, and cultural movements. It has helped inform and redefine how we view history and acts as a lens into the lives and infrastructure of the past